More on the Marshall-Hall scandals

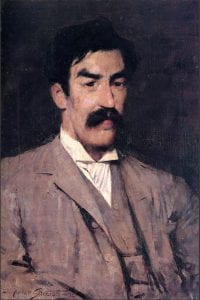

As if the life of the Melbourne conductor and composer G.W.L. Marshall-Hall (1862–1915) was not already noteworthy for its scandals, new revelations about his personal life have been uncovered in the papers of the National Archives, now available on Ancestry. Among them is an exchange of letters between him and his first wife to add to the collection of his letters published by Lyrebird Press in 2015.

Marshall-Hall and May Martha Hunt married in London in 1884. She came from a large family in the East End, where her father Thomas Willomat Hunt was a grocer, a trade that had also occupied her grandfather. Hunt had four children by his first wife, Eliza Morris, who died in 1862. May was born illegitimately to Martha Harvey in 1864 and the parents waited another seven years before marrying at St Jude’s in St Pancras in 1871. Both the East End origins and the irregularity of May’s birth would have meant that Marshall-Hall—whose father had been a magistrate, a barrister and owner of an eighteenth-century estate in Wiltshire—married well beneath him. But he also chose music as his trade, against his father’s advice.

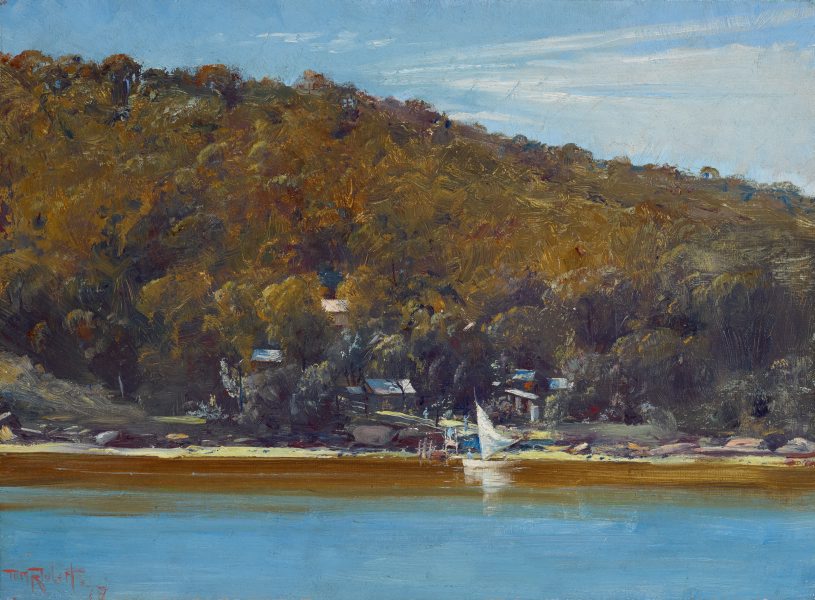

After their marriage Marshall-Hall and May lived in poverty in northwest London. A baby, Harold (named after the opera then in progress), born in late 1889, must have died soon after birth, so that at the time of their emigration to Australia they were childless. Their daughter Elsa was born on 17 August 1892 in Melbourne but not long afterwards May decided to return to London, although she had to wait until February 1893 for a berth on a ship. As Richard Selleck points out in his history of the university, Marshall-Hall’s letters to his friends and his eagerness to join them in their travels to Sydney and Launceston in January–February were not the actions of a husband in despair at the loss of his family. Rumours flared about Marshall-Hall’s attachment to the very beautiful Mrs Edith Eccles, a twenty-four-year-old singer married to the American-born Collins Street surgeon Dr Jacob Eccles. Selleck speculates that Marshall-Hall and Mrs Eccles were together in the summer of 1893–94 at the Curlew Camp on the shores of Sydney Harbour, where Arthur Streeton and fellow artists lived in tents and painted en plein air. Dr Eccles however must not have objected, because he wrote to the Age in support of Marshall-Hall’s treatment when he had a bout of diphtheria in 1898.

Marshall-Hall found a new lover not long afterwards and his only surviving son, Hubert, was born later that year to Katherine (Kate/Catherine/Kathleen) Hoare. Unlike May Hunt, Kate Hoare came from a distinguished Irish family, her father a well-respected engineer and surveyor in gold-mining towns and his father a solicitor in County Cork in Ireland. Kate was one of at least thirteen children of the engineer. Of them, her younger sister Lydia would marry the accountant Edgar Dyer, who was prosperous enough to own a house on Albert Rd, South Melbourne, and send his sons to Melbourne Grammar. Several of Kate’s sisters are mentioned in the newspaper account of Lydia’s wedding in 1900 but there is no mention of a Mrs Marshall-Hall or even of a sister of that name.

Kate must have been pregnant with Hubert in 1894 when Marshall-Hall requested leave from the university to return to London on “urgent and most important private matters”. He left in late July and did not return until mid-November, by which time Hubert must have been born (although no birth record exists). The newly discovered file in the National Archives reveals what this matter was: his wife May had petitioned the divorce court for the restitution of her conjugal rights, tendering a letter to “my dear husband” urging him to “take me home to you again and give me your love as of old before your mind was turned against me, for our little child’s sake let us forget the past and again find the happiness we have always known”. Some hint of her awkward status is found in a remark about how coldly society looked on women who lived apart from their husbands and the expression of her wish that “little Elsa” could take her “proper place” in society. Marshall-Hall replied on 19 September from Lewisham (on the other side of the Thames and well away from May’s relatives in Forest Gate). Addressing “my dear May” he wrote, “I have had from Edith a report of your conversation with her. I consider that you have misrepresented the situation entirely to your own interests. I am weary of these eternal threats and indignant at your unjustifiable detention of my property”. In this he appears to be more concerned to reclaim the score of his orchestral Idyl (later performed in London) than to see either May or his daughter. Instead he asked for a year’s separation, “but once for all I will not be forced by threats to lead a life which I am certain would be unhappier than before and impossible for both of us”. Well aware that she might take steps that would ruin his career he offered her 200 pounds per annum to leave him in peace. “I have been so nagged[,] worried and badgered that I no longer care what happens but will sacrifice everything to be free”. Two days later May began court proceedings which dragged on until May 1895, when the court demanded that Marshall-Hall pay her 300 pounds per year, 30 per cent of his salary (which the university was in the process of reducing, due to the Depression). In the meantime Marshall-Hall had taken on the financial responsibility for the university’s new Conservatorium, which opened in February 1895 in the Queen’s Coffee Palace on the corner of Rathdowne and Victoria St Carlton, opposite the Exhibition Gardens.

Shipping records show that May returned to Melbourne with an infant and a nurse in in April 1899 and left two months later, no doubt having discovered that Marshall-Hall was living with another woman and their son. The infant she brought with her was her son Norman, who when he married in 1930 left blank the section of the marriage form that required the name of his father. Perhaps he never knew who his father was. May died of cirrhosis of the liver in London in 1901, leaving Elsa (then aged ten) and Norman (three) in the care of her father’s younger brother, Thomas Glensor. Marshall-Hall and Kathleen Hoare married in 1902, two years after a prolonged scandal had ensured that Marshall-Hall lost his job at the university. Although his friends knew his family circumstances and one of them once wrote admiringly of the family’s contentment, it surely was impossible to hide from those who welcomed them in 1891 the fact that his wife had left him and that he had established a home with another woman. The effect of these events on the parties involved is incalculable: for the rest of his life Marshall-Hall worried about money and in two years in London lived in desperate circumstances while after his sudden and unexpected death in 1915 his wife’s terror at the prospect of the details of their relationship being known prevented anyone writing a biography. Hubert Marshall-Hall lived for the remainder of his life in England and named his daughter Georgina; Elsa returned to Australia, married and named one of her children after her half-brother Hubert and another after Marshall-Hall’s opera Stella. It remains a moot question whether a divorce in 1894 would have wreaked any more damage on Marshall-Hall’s career than he did himself in 1898–1900 by his outspokenness. Certainly, as this new letter shows, it might have saved him a substantial sum of money.