Teresa Balough remembers Burnett Cross

Teresa Balough has been writing about Grainger since she commenced a master’s thesis at the University of Kentucky in the 1970s. Her books on Grainger include A Musical Genius from Australia: Selected Writings by and about Percy Grainger (UWA, 1982), which for decades was the principal published source for Grainger’s writings. Her latest book, published by Lyrebird in 2020, is a collection of the correspondence of Grainger and Burnett Cross, co-edited with Kay Dreyfus. Here she remembers meeting Cross and his family.

You have a very longstanding interest in Grainger and his music. How did you first become acquainted with it?

I first heard Grainger’s music when I was an undergraduate student at the University of Kentucky. I was playing flute in the concert band when we were presented with a piece called Lincolnshire Posy by one Percy Grainger. I’m sorry to say that our director made fun of Grainger’s program notes regarding the old folksingers as he read them to us. I was enchanted by the music and asked my husband, Gregor Balough, if he had ever heard of Grainger. He replied with great enthusiasm that he had actually met Grainger when he (Gregor) was a violin student at the Chicago Musical College where Grainger was teaching summer courses. He said that Grainger appeared like a ray of sunshine walking down the halls of the College, smiling and greeting everyone he met.

How did you become acquainted with the family of Burnett Cross? Are there members of the family still living who remember him?

As a graduate student in musicology at U.K., I learned that there was not much written about Percy Grainger at that time, so I decided to do my master’s thesis on Grainger. I wrote to his widow, Ella Grainger, and asked what aspect of his music she would like to see researched. She responded by graciously inviting me to spend several days with her in White Plains, New York and suggested that what was really needed was a catalog of Grainger’s music. During the course of my visit with Ella that summer of 1971, she took me to meet her husband’s close friend and colleague in Free Music, Burnett Cross. We spent a very pleasant evening at Burnett’s apartment, where he played reel-to-reel tapes for us of a number of Grainger’s compositions, including The Warriors. Several years later I was invited to become a member of the board of what was then called The Percy Grainger Library Society, of which Burnett was also a board member. This entailed visits to New York from my home in Virginia; and it was during these visits that I became acquainted with Burnett’s brother Howard and his sister-in-law Fran, with whom I shared meals and conversation at their home in Hartsdale, New York. Howard passed away shortly after Burnett’s death and Fran passed away in 2019; but their children, Howard Jr., Doug, and Pam are all living and have many recollections of the wonderful uncle who was like a second father to them.

Did the family store or collect much material relating to Cross’s collaborations with Grainger?

When Burnett passed away in 1996, Howard and Fran asked me to go with them to Burnett’s apartment in Hartsdale and sort through his papers, keeping any material relating to Grainger as they were concerned that it might otherwise be lost. This was the source of the copies of letters between Cross and Grainger which appear in Distant Dreams and the photos, most taken by Burnett himself, of the progress of the Free Music Machines. There were also copies of programs from Grainger concerts and promotional flyers and other miscellaneous correspondence. All original letters between the two men had, of course, already gone to the Grainger Museum.

What remains in Grainger’s White Plains house of the Free Music experiments?

There is one remaining Free Music machine at the Grainger House in White Plains, New York, the February 1950 instrument labelled “Gliding tones on whistle, notes on recorders, produced by holes & slits cut in paper rolls,” a photograph of which appears on page 26 of Distant Dreams and also on the front cover. The Grainger Society is currently applying for a grant to conserve this machine, which would allow it to be put on display in the Grainger House.

Why do you think Grainger and Cross preferred to work on their own without communicating with other composers interested in new technologies and sound art? Was it because they simply enjoyed building and experimenting for the sake of it?

I think that the reason Grainger and Cross worked alone is because the sound that Grainger was looking for was so different from what other composers of the time were interested in. They did, in fact, begin their collaboration by seeking out the expertise of others in the field but soon discovered that the ideas put forward by those they contacted would either be too cumbersome to be useful or would not meet the required specifics Grainger had in mind. Burnett once remarked that he felt that other composers using mechanical or electrical means to create experimental music were more interested in finding something useful compositionally from existing machines while Grainger had in mind all along the exact sounds he wanted and then had to build something capable of creating those sounds.

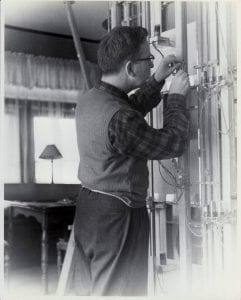

Photo: Grainger at Interlochen, Michigan (Grainger Museum). Burnett Cross makes an adjustment to the “Kangaroo-Pouch” Tone-Tool, 1952 (Cross Estate).

Categories